Are humans using artificial intelligence better at making unbiased choices? Is it enough to have humans oversee AI decisions to ensure fair and balanced decisions are being made? If yes, how? What does it take for systems to be trustworthy and fair?

What is the problem?

“Human oversight aims at avoiding negative consequences from badly programmed AI”

EU AI Act, Article 14 - Human Oversight

In recent years, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become increasingly used to aid human decision making in areas of great societal importance. While it can help in faster decision-making and reducing human cognitive biases and limitations there are concerns about its potential to discriminate. This is where human oversight is required, to minimise the risks to fundamental rights enshrined in the General Data Protection Regulation GDPR (Article 22) and the AI Act.

But can human oversight effectively prevent discriminatory outcomes from the use of AI?

What is the project about?

This is where our study on “Understanding the Impact of Human Oversight on Discriminatory Outcomes in AI-Supported Decision Making” comes in.

Using a mixed-method approach we paired quantitative behavioural experiments with qualitative analyses through interviews and workshops. We explored how human overseers interacted with AI-generated recommendations and the underlying biases that influenced their decisions, asking 1400 professionals in Italy and Germany, to make hiring or lending decisions with either fair or biased AI-generated recommendations.

We discovered that human overseers largely ignored AI advice and did so in line with their discriminatory preferences (e.g. considering some nationalities more reliable than others). This fed a larger contextualised discussion in a follow-up study with the study participants. Qualitative insights from interviews, group sessions and workshops with those participants revealed the background to those decisions in terms of bias awareness, fairness perception, and ethical norms.

What we did

What would a fairer hybrid system of algorithm-supported human decision-making process look like?

After the first study, we ran a collaborative speculative workshop with a multidisciplinary group of researchers and actors in the AI fairness debate to discuss the results of our study and ideate interventions to mitigate human and algorithmic biases in AI-supported decision-making.

Experts from diverse backgrounds, including AI, ethics, design, art, science, philosophy, and sociology shared their perspectives, ideas, and visions on the topic. The discussion highlighted the need for a dynamic approach to fairness in AI and the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in addressing discriminatory outcomes.

Many thanks to: Valeria Adani, Egon L. van den Broek, Raziye Buse Çetin, Filippo Cuttica, Manuel Dietrich (Honda Research Institute EU), Abdelrahman Hassan, Tim de Jonge, Suhair Khan, Senka Krivic (Faculty of Electrical Engineering, University of Sarajevo), Christina Melander (DDC – Danish Design Centre), and Giada Pistilli (Hugging Face) for their invaluable input and expertise.

What we learned

"Experts are calling on the internal moral compass of each and everyone, including policymakers. Look into your dark side through AI."

a workshop participant

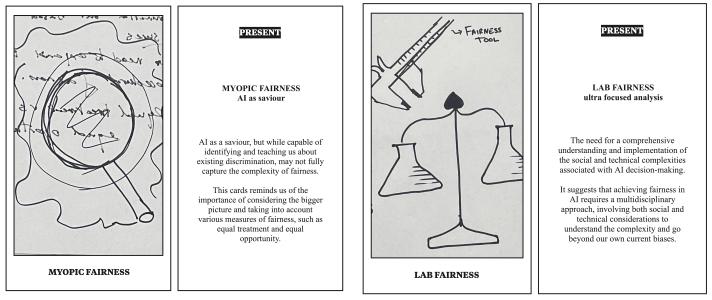

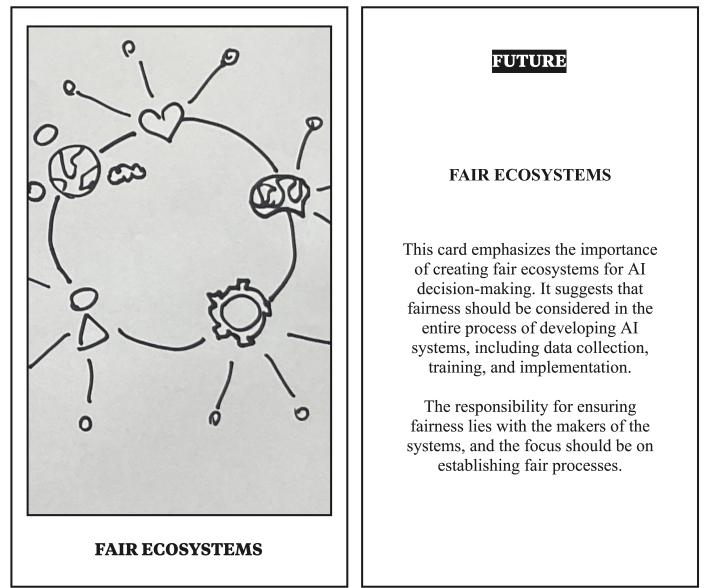

This prompted us to analyse and discuss how institutional decision-making and fairness connect. We focused on specific examples of recruitment and loans, which can lead to potential loss of opportunities for certain individuals. Introducing AI into recruitment and lending decisions helps shine a light onto the biases and prejudices that drives our decisions, as well as those of the AI. For this study, we trained two AI systems to generate recommendations, one ’fair and one ‘unfair’. We defined fairness by training the ‘fair AI’ to exclude protected characteristics from the dataset (e.g not take gender or nationality into account when making a decision), where individuals and their profiles' characteristics are the unit of analysis. During our discussions, we explored this definition of fairness and the evolution of the concept using tarot cards to symbolise past, present, and future ‘readings’.

One of the main outputs of the discussion was the shift of fairness from a static to a dynamic process that needs continuous practice. We discussed how ensuring fairness is not just the responsibility of AI developers, but it is also about establishing fair process by those who use the AI. The experiment initially focused on discrimination against individuals, but we also discussed systemic aspects of discrimination.

This is particularly relevant for a European organisation, as addressing individual discrimination is not enough if the system itself does not change. Fairness depends on specific circumstances and characteristics involved, and achieving fairness in AI requires a multidisciplinary approach that considers both social and technical factors. Building collaborative fairness requires awareness of when the system is failing and when humans are failing the system.

What's next?

So, what does the future of European AI and ethics look like? Stay tuned with us for more on this exciting field of study!

- More about Design for policy: Design for Policy - European Commission (europa.eu)

- Discover the work of the Competence Centre on Behavioural Insights

- More about the JRC’s AI expertise: European Centre for Algorithmic Transparency (ECAT)

Details

- Publication date

- 22 March 2024

- Author

- Joint Research Centre

- Departments

- Directorate-General for Digital Services, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology

- EU Policy Lab tags